By, Mike Kennedy

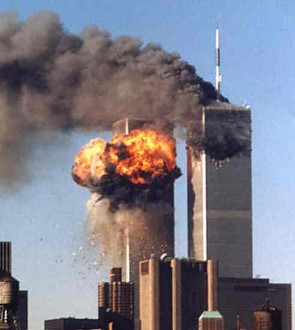

This article concentrates on the underpinnings of terrorism with the hope of providing information that could be helpful in preventing future acts. It is proper and fitting to begin by referencing the legal definitions of terrorism. By referencing the legal definitions of terrorism, we can separate these from violent acts (e.g., criminal behaviors often labeled as terrorism by the media) that do not meet the legal definition of terrorism. This is not to downplay egregious acts, but to place them in the legal category in which they fit. Distinguishing terrorism from acts of violence also clarifies public perception of terrorism. Legally though, the definitions are clear. Under 28 CFR 0.85 1, terrorism includes the unlawful use of force and violence against persons or property to intimidate or coerce a government, the civilian population, or any segment thereof, in furtherance of political or social objectives. United States Law, Title 18 U.S.Code §2331 2 further defines terrorism as, "both international and domestic."

Social scientists and psychologists have studied terrorists thoroughly. Early work focused on understanding violence and the propensity of the human being to commit it. Freud, the father of psychoanalysis, believed that the propensity to commit violence is with us from birth. Freud characterized violence as a natural impulse or inclination most people outgrow as they develop (Borum, 2004).

Frustration-aggression theory holds that aggression is always produced by frustration, and frustration always produces aggression. It may hold weight for some people, but it is also clear that some aggressive people are not frustrated and some frustrated people are not aggressive. Social learning theory suggests behavior is learned and continues or ceases based on the consequences (reward or punishment) of that behavior. Social learning also holds weight for some groups and is demonstrated through certain terrorist group’s use of children to commit heinous acts. Children are rewarded for committing these acts; therefore, the behavior is said to be reinforced. Similarly, the families of suicide bombers and terrorists are often paid handsomely by entities sponsoring terrorism. When terrorists attempt to leave a group, they are often deemed unfaithful and are killed by others in the organization – in other words, their behavior is punished. When other group members witness these rewards or punishments they learn how to be violent, to whom to be violent, why it is justified, and when it is appropriate (Borum, 2004).

At its core, cognitive theory of aggression holds that people’s interactions with the environment are grounded or rooted in how they see it and their understanding of it. The theory suggests that as people observe their environment and interact within it, they draw a cognitive map of that environment based on what they have observed. Their perceptions are, of course, subjective and form the core of their behavior; it isn’t necessarily an objective perception of reality. Research also suggests aggression is affected by perceptions of intent (Borum, 2004). Research concerning the cognitive theory of aggression reveals two predominant cognitive/processing deficits in highly aggressive people. The first is that these people are unable to find conflict solutions that are non-violent. The second is that their perceptions are excessively sensitive to hostile and aggressive environmental cues, especially those that are interpersonal (Borum, 2004).

Empirical studies have also yielded insights into the identification of risk factors for violent behavior; not necessarily terrorism; that are useful. For clarity, a risk factor is any factor, that when present, makes violence more likely than when it is absent (Borum, 2004).

Modern research focuses solely on gaining an understanding of terrorism and notes key factors that may lead to a person becoming a terrorist: perceived injustice, identity, and belonging. A desire for revenge is a common feeling when someone feels they have been wronged. This is even stronger when a person feels that the injustice was not done just to them, but also to their people. These perceptions of injustice come in the form of economic, ethnic, racial, legal, political, religious, and/or social reprisals.

Research suggests three factors: injustice, identity, and belonging commonly co-occur with terrorists. Some researchers see the three factors working together to produce an effect greater than any one factor alone; and, suggests it is the root cause of terrorism and establishes the strongest underpinning for it.

Reference: Borum, R. (2004).Psychology of Terrorism.

Footnotes

1Code of Federal Regulations 28 CFR 0.85

2Title 18 US Code 2331

3 In Freudian psychology, displacement is an unconscious defense mechanism whereby the mind substitutes either a new aim or a new object for goals felt in their original form to be dangerous or unacceptable.