.png)

Are you a first responder who is already using Unmanned Aircraft in your department? If so, what would you say is the single most difficult challenge in using your unmanned air vehicle (UAV): Getting department approval and funds for purchase? Training and maintenance costs? Identifying and keeping trained operators? Finding room in your vehicle for two extra hard cases?

Those are all challenges, of course. But if you are up to date on changes in UAV use around the country, you will probably say that the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) is one of the biggest challenges your department faces in employing an unmanned air system (UAS) to support first responders. And if you are unaware of how the FAA views unmanned aircraft use, we hope this helps to save you some big trouble in the future. Let’s see how FAA affects first responder UAV use. A short summary of FAA operations may be helpful.

“We’re the FAA and we’re here to help you!”

FAA is responsible for the National Airspace System (NAS) and everything that flies inside it. Simply put, the NAS is all of the airspace from ground level to outer space that is NOT over a military installation or beyond the United States territorial waters. All aircraft—commercial jet airliners, general aviation, news helicopters, crop dusters AND your 4 lb UAS are regarded alike and must all conform to the Federal Air Regulations (FAR). First and foremost, FAA requires an aircraft (manned or unmanned) to have a way to “sense and avoid” collision with other aircraft while in flight. In the case of manned aircraft, the human pilot and crew, along with airborne and ground radar, perform the sense and avoid. Transponders carried aboard manned aircraft send an identifying code that air traffic controllers can see on their radar screens (sense). The radar operators can tell if two aircraft are in danger of a collision. Radio communication from ATC and aircraft can get the pilots to maneuver away from a collision situation (avoid). This works very well—so well that in most cases, outsiders never know it’s happening. But what about a UAV that may be too small to carry a transponder?

The FAA will let us humans provide the sense and avoid for our UAV. In most cases, UAV use is limited to line-of-sight from the pilot and visual observers. In this way, the UAV location and flight direction is constantly monitored by the flight crew. Visual Observers, supporting the pilot, watch the UAV as he/she are flying. They also watch out for manned aircraft that may enter the flight area (sense). If an airplane or helicopter approaches the UAV, the UAV pilot can take evasive action to avoid the possibility of a collision. If the UAV is going to fly higher or further than the ground observers can see, an observer riding in a chase aircraft can follow the UAV to maintain sense and avoid. In cases where a UAV can carry a Mode/C or other transponder, observable on air traffic control radar, extra permission may be given by FAA. Speaking of permission, do you know about the Certificate of Authorization or COA that FAA requires before any agency can legally operate their UAV inside national airspace?

To operate any UAV or UAS in the national airspace, FAA requires that you apply for and are approved for a Certificate of Authorization waiver, or COA. This requirement includes the U.S. Air Force, FBI, NASA, and every other government agency, called by FAA a “public entity.” Included in the public entity group are police and fire departments, state and local government agencies, and public colleges and universities. The key here is “public.” A public entity is backed by their larger governmental agency and this is what allows them to self-certify the airworthiness of their UAV. Non-government agencies and non-public universities do not qualify to apply for a COA. How can non-public agencies and businesses fly their UAV in the national airspace? Well, right now, unless they pay for and undergo a very costly and time-consuming airworthiness application process, they can’t. Things will be changing in coming years, promises FAA, but have not changed yet.

By far, universities have the most COA’s of any class of public entity with the exception of our armed forces. Universities conduct research on UAV sensors and control systems, agriculture monitoring, and many other areas. Law enforcement agencies, fire and emergency services currently trail in the number of COA’s issued by FAA. As mentioned last month, the Miami-Dade Metropolitan Police Department is a leader in law enforcement COA’s and UAV use. They worked with FAA to develop procedures that allow the UAV to be operated (with limits) throughout their jurisdiction. Their operation is a success story and they helped shape the rules for other law enforcement agencies to successfully operate UAS. A few words about what exactly a COA is may be appropriate here.

What Exactly Is a COA and Why Do I Need One?

The COA is basically a waiver that allows the applicant agency to operate a particular UAS at a particular location (or area) up to the approved altitude. Unlike a drivers’ license that allows the operator to drive any vehicle anywhere, the COA is only good for a particular UAV. You can have a fleet of identical UAV’s that have the same guidance system and other components that make up its flight characteristics. Your application will be for a particular area. If you want to fly outside of the approved area, you have to apply to FAA for modification or if extremely different, another application. More about this later. In your COA application, you must provide a letter on department letterhead stating how you will ensure that your UAV will be airworthy as well as operated and maintained in safe condition. Another letter will be required from your state’s Attorney General affirming that your department is a federal, state, or local government agency. Extensive details about the aircraft performance, description, control links, flight procedures, and aircrew qualifications are required. A description of your proposed area of operations, including latitude, longitude, and elevation of boundary corners is also required. Your operation area should be away from population centers to reduce the risk of the UAV injuring a person if something goes wrong. More on this later. You must also be greater than 30 nautical miles from one of the 35 Class “B” major airports in the U.S. (Atlanta, Boston, Charlotte, New Orleans, etc.). You will find much useful information on the aircraft sectional charts that manned-aircraft pilots use.

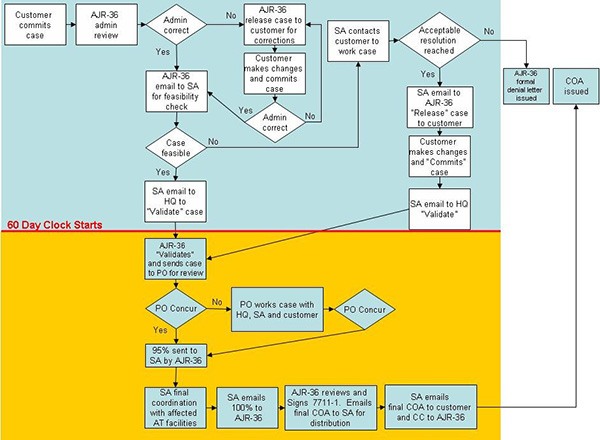

A COA can be good for up to two years and is renewable. Several years ago, the application process was quite mysterious—with no guidance on what information was expected from the applicant—and applications took almost a year. FAA is now approving most COA applications in 60 days after their initial review for completeness and accuracy. The people reviewing and approving these applications are veteran FAA professionals and are very willing to help with questions. The following flow chart shows the FAA COA Application Process.

During the application process, FAA will provide status updates as your application moves through the five approval and review phases. Final phase is the signature phase which results in you receiving an email with the approved COA and operating requirements. These are about 25 pages—some of which you provided to describe your operations and procedures. Receiving this approval email is a pleasant experience which never fails to thrill.

Special Requirements for First Responder COA Applications

Most COA applications are for operating a UAV away from populated areas. These are more readily approved by FAA, since they pose lower risk of injury to persons and property. However, a law enforcement agency, fire department, or emergency services department will want to have their entire jurisdiction approved for UAV operation. This is natural since an emergency could happen anywhere in your response area. Because this jurisdiction WILL include populated areas, FAA has a two-stage approval process. In the first phase, a remote site is chosen for training and familiarization flight of your UAV. Upon becoming competent to operate your UAV safely, FAA will come and observe your operations (like a “check ride”) and approve you to apply for a Phase 2 application. This phase 2 application will cover your jurisdiction and basically allow you to operate your UAV throughout your response area as emergency or need arises. There are some limitations here that FAA may impose based on each application and jurisdiction.

We hope these brief explanations have been helpful—and not caused your head to explode. Dealing with the FAA regulations are just one more set of requirements and there is help available in meeting them. Next month, we will discuss procedures, aircrew (pilots and visual observers) requirements and where to find helpful resources in applying for a COA. Until then, be safe out there!

Law Enforcement Agency in the news: Mesa County, Colorado Sheriff’s Department

Pictured Above: Deputy Josh Livingston and Deputy Amanda Hill with Draganflyer X6 UAV (photo by Mesa County Sheriff’s Office).

Click here to read more about how this progressive department is a leader in law enforcement use of UAS.

Dave Price is Senior Research Technologist at the Georgia Tech Research Institute in Atlanta, Georgia. He has 20 years’ experience with unmanned aircraft and 35 years as a researcher for Georgia Tech. Mr. Price flies both fixed wing and rotary-wing UAS for GTRI. He works closely with FAA to obtain Certificates of Authorization for approval to operate UAS in the national airspace system. He recently flew the AirRobot 100 in support of Barbour County (AL) SWAT at the SETAC test site in Eufaula, AL, where unmanned air and ground systems were used in a simulated school shooting exercise.